In my world of civil and environmental engineering design there is a lot going on now with new ideas, tools and automation to make our designs quicker, cheaper and hopefully better. I thought it would be fun to think about some of the innovations that have shaped engineering over the past 150 years. I'm not an expert on engineering history, so I'll be leaning heavily on my old buddies Google and Wikipedia for help (hey, maybe I should use the Encyclopedia Britannica for nostalia!). Here goes...

Surveying

OK, so I thought I'd look back in history and find that the theodolite - mainstay of surveyors throughout the 20th Century - would have been a relatively new invention, but according to Wikipedia it was invented by a fella called Leonard Digges in the 1500's! Now according to Encyclopedia Britannica their use for surveying didn't really take off until the invention of log tables in 1620, but what the heck! I guess these disruptive inventions are WAY older than I thought. Maybe it's time for a new disrupter...

Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAV) aka "drones" are in the news a lot these days. In my own firm, we actually have a group focused on inspections using drones. Pretty cool stuff. Their application for surveying is a no-brainer. They can produce accurate surveys in a fraction of the time. Here's one example.

The other cool innovation is LIDAR/laser scanning which enables existing structures to be captured in digital format and translated straight into models and drawings. Now couple this with UAVs and we're in Sci-Fi land already!

Drawings

Aha, now this time I am in the 150-year window. Back in the 19th Century the advent of blueprints enabled engineers and architects to make copies of drawings more easily and with greater accuracy. To make these drawings, though, required massive teams of draftsmen in their drawing offices.

Fast forward to the end of the 20th Century and Computer Aided Design (CAD) emerges on the scene to make the production and reproduction of drawings simpler (bye-bye drawing office, hello CAD-Tech). The next step was to produce 3-D "models" instead of simple drawings, from which drawings and other information can be pulled.

Finally, we can now link these models to all sorts of engineering, costing and other design information in "Building Information Modeling" (BIM). Bippty-boppity, BIM! One model to rule them all!

Fast forward to the end of the 20th Century and Computer Aided Design (CAD) emerges on the scene to make the production and reproduction of drawings simpler (bye-bye drawing office, hello CAD-Tech). The next step was to produce 3-D "models" instead of simple drawings, from which drawings and other information can be pulled.

Finally, we can now link these models to all sorts of engineering, costing and other design information in "Building Information Modeling" (BIM). Bippty-boppity, BIM! One model to rule them all!

Process Design

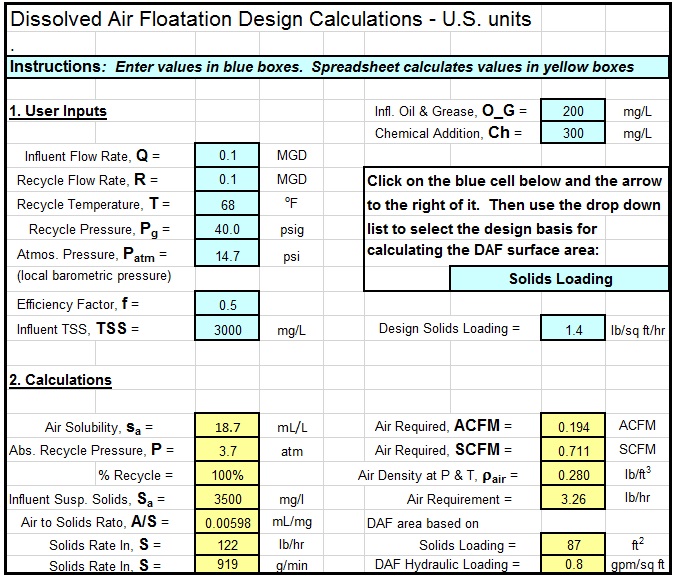

And now to my fun area of design: selecting and sizing wastewater treatment processes. Wastewater treatment technologies are roughly 150 years old, so it's interesting to think about how process design has changed over the years. Even up until recently, hand-calculations to size major process units were not uncommon. Certainly spreadsheets enabled these calculations to be done more efficiently and effectively through the 80's and 90's. There are many examples and even books written on the topic!

And now to my fun area of design: selecting and sizing wastewater treatment processes. Wastewater treatment technologies are roughly 150 years old, so it's interesting to think about how process design has changed over the years. Even up until recently, hand-calculations to size major process units were not uncommon. Certainly spreadsheets enabled these calculations to be done more efficiently and effectively through the 80's and 90's. There are many examples and even books written on the topic!One of the major limitations of spreadsheet calculations for poop plants (sorry, I mean water resource recovery facilities - tough to break old habits), is that treatment facilities are quite dynamic, with fluctuations in flows and waste constituents over daily, weekly and seasonal patterns. It's tough to do spreadsheet calculations on dynamic systems.

| New kid on the block: http://www.dynamita.com/the-sumo/ |

Future Disruption

OK, no self-respecting blog on innovation and disruption can resist taking a wild stab in the dark on future trends, so here goes!Big data? Hmm, not sure: we have a lot of bad data. Analytics? For design...not really. Artificial intelligence? Ooh, now you're talking. So, starting from a UAV scanning an area, or existing treatment plant, to producing a BIM model seems like a pretty short couple of steps. The pieces and parts are there already; we just need the smarts and rules to link them up. But wait, we need super-smart process engineers to run the simulations, right? For now, yes. But even this piece can be automated (we're not as smart as we seem). To see the future, check out this cool tool developed by Organica. My understanding is that it's not fully automated yet, but not far off. The day may come when I can hang up my slide rule, burn my log tables and let robo-engineer do all the hard work!